Editor's note: This story is part of The Marathons Series, a collection of articles written by faculty and students. It's a space to talk about work in progress and the process of research—think of it as the journey rather than the destination. We hope these stories help you learn something new and get in touch with your geeky side.

In January 2010, I boarded a plane to Dakar, Senegal for the first time. My plan was to spend a few months studying African dance, which, to my mind, signified a limited set of traditional dances performed to djembe drums. I was largely inspired by an African dance class I took during my senior year of college—the first and only time such a class was offered during my four years as a dance major in a BFA program that emphasized Western modern dance.

In Dakar, thanks to connections established through my college instructor, Djibril Camara (former member of the Senegal-based Ballet de l’Afrique noire), I hit the ground running. I relished daily classes, intensive workshops, and stunning performances. I extended my return ticket—and extended it again—ultimately staying for almost a year (and returning the following year, and the year after that).

It didn’t take long to see that there was so much more to dance in Senegal, and Africa broadly, than the narrow ways in which so-called “African dance” is often transmitted west of the Atlantic. I was most struck by what people I met referred to as la danse contemporaine (contemporary dance), which I saw as cutting edge, socially engaged choreography that seemed to share an ethos of experimentation with the modern dance form that I’d previously understood to be an exclusively Western construct.

My first encounter with contemporary dance in Dakar was largely due to the pioneering work of Congolese choreographer Andréya Ouamba, whose intensive workshops Ateliers Expérience et Corps (AEx-Corps) I fortuitously stumbled upon a few months into my first trip.

Fifteen years and more international flights than I can count later, my book, Dancing Opacity: Contemporary Dance, Transnationalism, and Queer Possibility in Senegal, is set to be published by the University of Michigan Press this fall. The book examines artists’ strategies for artmaking in the context of ongoing coloniality: How they navigate the global contemporary dance circuit from economically marginalized locations, how they contend with expectations of Black African performance on global stages, and how they subtly push back against the present-day anti-LGBTQ climate in Senegal.

Although Senegal has a long history of acceptable, and even valued, gender variance and same-sex sexualities, a variety of complex phenomena caused homophobia and transphobia to proliferate there since 2008. Whereas the codes and conventions of gendered expression deemed appropriate in Senegalese public spaces became more limited over time, a sense of openness and liberation pervaded contemporary dance spaces, amounting to what I felt as a visceral distinction between the public sphere and the dance studio or stage.

Developed through an ethnographic method (the systematic study of culture through observation and participation) of dancing and dialoguing with artists and supplemented by historical research, Dancing Opacity chronicles the critical work of Ouamba, Germaine Acogny and her international dance school École des Sables, Fatou Cissé, Ousmane Noël Cissé, and several others.

The book argues that contemporary dance artists based in Senegal strategically evade both universalized narratives of African performance and state-sanctioned regulations governing gender and sexuality. They pursue opacity in their teaching and performances that put forth ambiguous alternatives to the imagined corporealities forged through the colonial encounter and its afterlives.

Contemporary dance is, I suggest, a privileged arena where experimentation with queer aesthetic possibilities is permissible in contexts that otherwise disavow queer life.

I did not travel to Senegal with the intention of seeking out opacity in creative work, nor did I anticipate a research project or academic career of any kind during my first few stays. Instead, I was led down this path over the years of dancing alongside and learning from people there.

As I crisscrossed the Atlantic in my mid-twenties, I became increasingly aware of the gaps in my dance education in the US, particularly the absence of contemporary artists from the Global South. This encouraged me to pursue a PhD and eventually to write this book as a way of contributing to existing conversations in the field of dance studies.

Authoring a book about African subjects as a white North American risks perpetrating harm. Although my goal has always been to shed light on marginalized artists’ creative ingenuity and astute navigations of power, the possibility that the text in some way misrepresents them due to my privileged racial and national identities haunts me. While the book is on the cusp of publication, I have not fully resolved these tensions.

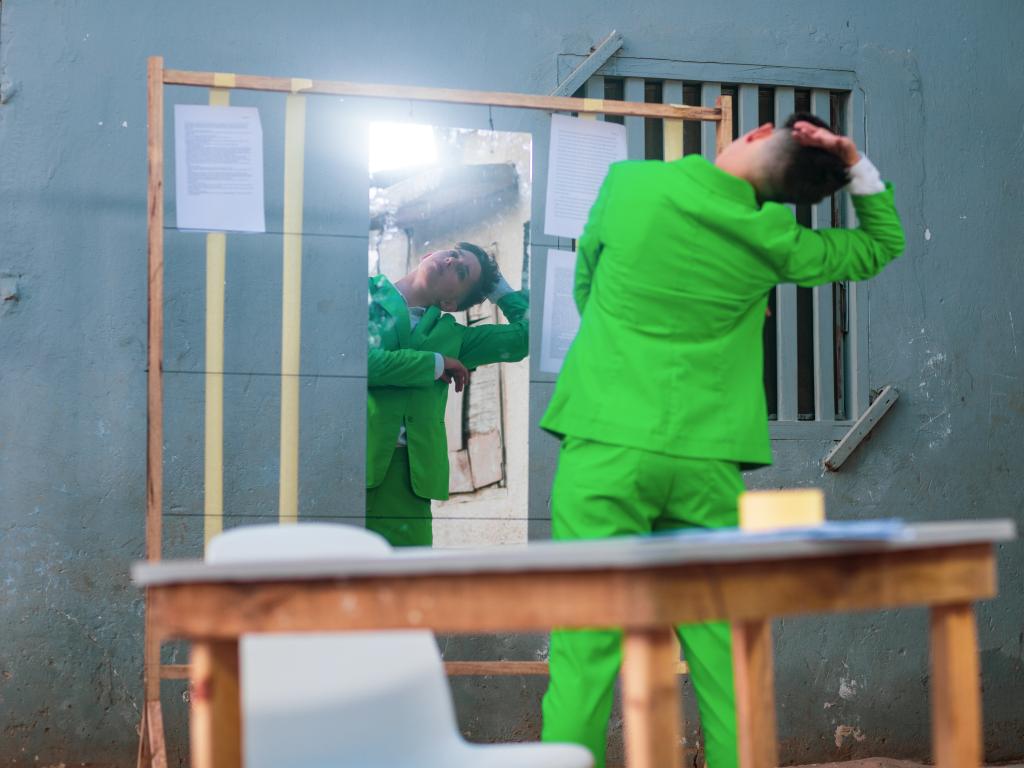

In fact, my ambivalence became the topic of a new choreographic exploration with Ouamba who, in 2022, proposed working with me on a solo that would investigate my positionality as a white researcher in Africa. We began work the following year, delving into a creative process that centers themes of indecision, discomfort, and global discourses about race. This led to an invitation from Fatou Cissé to perform a work-in-progress at her street performance festival La ville en mouv’ment (The City in Movement) in June 2023.

Swanson dances her research as part of a street performance in Dakar in 2023.

To embody these tensions, engage in a creative process with one of the artists who inspired my research agenda, and then perform a work-in-progress in Dakar was in a sense to come full circle: Having danced in Dakar prior to researching dance there, I was now dancing my research. I do not mean to suggest that this performance somehow eradicates the potential harm of misrepresenting racialized others; one cannot simply dance away the legacies of colonialism and white supremacy.

Instead, guided by performance studies methodologies elaborated by Dwight Conquergood and D. Soyini Madison, the performance as an extension of the research process has served as an opportunity to collaboratively lean into questions afforded by the research, to dwell in a space of questioning through creative practice.